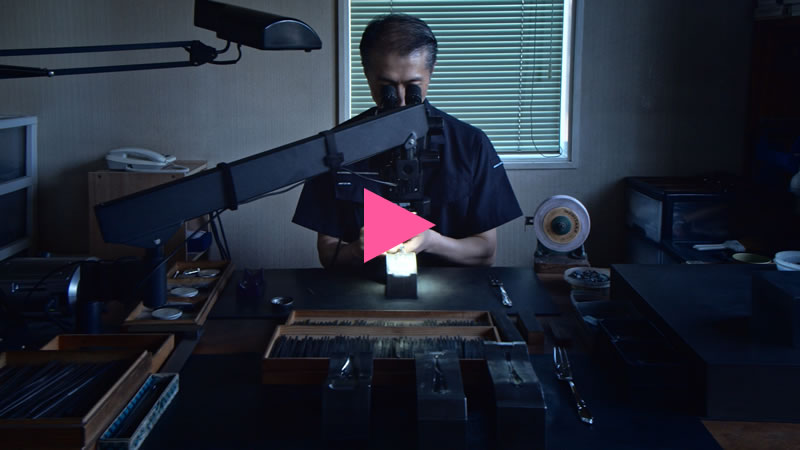

The Japanese straight razor (“wa-kamisori”) and Japanese spring scissors are two tools unique to Japan. Although Japanese razors were originally used by samurai to shave the tops of their heads, after the start of the Meiji period (1868 ? 1912), they came to be predominantly used as beard-shaving tools in barbershops. Japanese razors are made by forge welding a steel blade onto a bar of iron. The traditional forging process is done entirely by hand. Once sharpened, the blade boasts a super thin, micron-width edge capable of cutting hair on contact.

Today, Tsubame-Sanjo is home to Japan’s last razor smith. Inquiries from people seeking their famously sharp blades continue to arrive from throughout Japan.

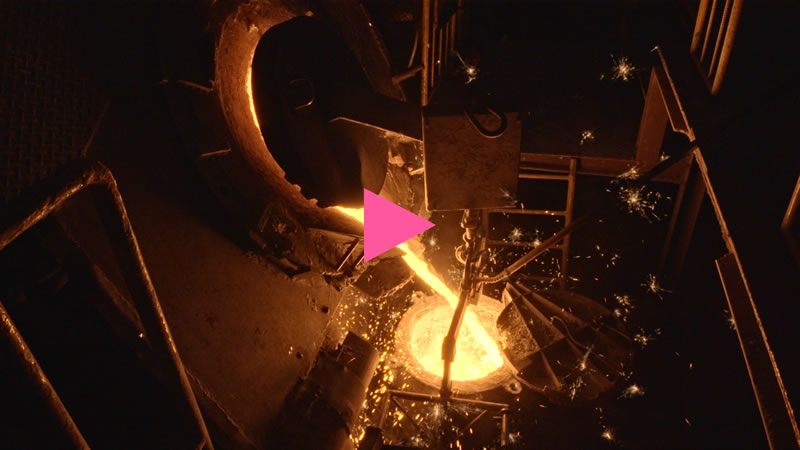

In the early 1930s, Tsubame-Sanjo’s forging and metal polishing technologies were combined to manufacture work tools. Along with Osaka, Tsubame-Sanjo is one of Japan’s biggest producers of work tools and exports large volumes of pliers, wire cutters, and screwdrivers. Pliers are manufactured by shaping a piece of red-hot steel with a die and hammer. The process requires precision-hammering, and experience has a significant impact on plier quality. Moreover, the blades couched at the pliers’ base must be filed and polished by hand―intricate work that cannot be easily mechanized.

Hammers are one tool that humans have used since ancient times. The manufacture of sledgehammers (“genno”) and other types of hammers in Tsubame-Sanjo began spontaneously in the 1920s. At the time, hammer manufacturing involved using a double jack to beat crude iron―typically collected as waste from metal ships―into the shape of a hammer. A steel cap would then be forge-welded onto the hammer face and filed down. With technological advancements, it soon became possible to manufacture full steel hammers out of steel rod. The method of shaping the metal also shifted from manual double jacks to motorized belt hammers, drop hammers, and air hammers, which led to an increase in productivity. Sledgehammers remain an essential tool for many craftspeople and continue to support Tsubame-Sanjo’s blacksmiths today.

Pincers are a type of clipping tool used to cut wire and nails. Local production is said to have begun in the Taisho period around 1910 when a traveling merchant from the Kansai region brought a pair to Tsubame-Sanjo. After WWII, military demand for pincers dried up, and general market demand shrank due to the appearance of cheap, mass-produced nippers. Around 1950, one pincer manufacturer, Suwada, used their knowledge to begin manufacturing fingernail clippers. Later, in 1956, they expanded production to bonsai pruning shears. Today, Suwada makes over 60 varieties of bonsai shears―more than any other manufacturer in Japan.

Tongs are a blacksmithing tool used to grip, lift, bend, and stabilize hot metal workpieces. While the number of craftspeople capable of forging tongs is in decline, demand for custom tongs has not disappeared. Today, orders for forging tongs of every type find their way to Tsubame-Sanjo. Incidentally, Tsubame-Sanjo’s blacksmith apprentices are said to begin their training by forging their own pair of tongs.

From the 1900s to the 1920s, bearded carpenter’s axes (“masakari”) were produced in large numbers for logging. Masakari come in many lengths and sizes. Recently, hatchet-sized masakari have found new demand as popular camping tools in the wake of the outdoor leisure boom. Another Japanese axe, the standard forest axe (“ono”), is a versatile tool used for felling trees, cutting branches, and splitting wood. For traditional ono, a total of seven grooves are carved into the head of the axe on either face. Each groove represents a divinity and acts as a prayer for safety during dangerous work. From this symbolism, ono have also come to be used as ceremonial tools for cutting mooring ropes at nautical launch ceremonies. Ono come in many shapes, sizes, and weights. While masakari have wide, bearded blades, ono have narrow heads that fan outward.

U-shaped Scissors

Japanese U-shaped spring scissors are unique tools that can be used with an easy squeezing motion. Perfect for detail-oriented handicrafts, they were once common in both textile and clothing factories. At the peak of production, Tsubame-Sanjo was home to around 340 scissorsmiths.

Hand-manufactured one by one, Japanese scissors are made by forge welding steel blades onto a bar of iron. The ends are then bent together and carefully aligned.

Tsubame-Sanjo’s last producer closed shop several years ago. However, inquiries from people seeking their famously sharp blades continue to arrive from throughout Japan.

The production of carpenter’s planes in Tsubame-Sanjo can be traced back to 1882. The plane is a wood shaving tool that comes in a variety of shapes and sizes. Japanese planes are composed of a metal blade couched within a wooden body, and plane manufacturing is a collaborative process between a metalworker and a woodworker. A quality plane needs both a sharp edge and a wooden body that compliments the blade’s specific thickness and angle. Today, this know-how is being applied to new products, such as bonito shavers for the home kitchen.

The production of chisels in Tsubame-Sanjo can be traced back to 1882. Carpenter’s chisels are versatile tools that can be used to split, shave or carve holes in wood. Among all of the tools in the carpenter’s toolbox, chisels are said to boast the greatest diversity. They are essential for shaping the complex joints of Japanese timber-frame architecture and are also used for minute adjustments and delicate finishing details. While there were once as many as fifty workshops in Tsubame-Sanjo specializing in carpenter’s chisels, today only six remain. However, custom orders for chisels come from throughout Japan, along with requests for hand axes, spear-planes (“yari-ganna”), and other wood carving tools used by traditional shrine carpenters. In recent years, these same workshops have attracted custom orders from violin and guitar manufacturers overseas.

With the forging of knives and farming implements arose a new demand for wooden handles in Tsubame-Sanjo. At first, no craftspeople were producing wooden parts, and tool users were left to make and fit their own handles. However, staring in around 1860, the region’s first “handymen” offering handle fitting services appeared. These craftspeople were the forerunners of Tsubame-Sanjo’s woodworkers. Records from the time mention one workshop, Sasugaya, which specialized in handles for small knives.

In the late 1880s, production of farming implements and bladed tools soared. Demand for wooden parts continued to rise, and full-time woodworkers appeared. Today, Tsubame-Sanjo’s woodworkers use both traditional tools from local forges and state of the art machinery to produce wooden products that meet the needs of the times.

Kiridashi are a representative type of Japanese single-edged knife. Small wood-carving knives with sharp, diagonal blades, kiridashi were once ubiquitous in everyday life as a common pencil-sharpening tool. However, with the spread of utility knives and pencil sharpeners, demand for kiridashi knives disappeared from daily life. Today, kiridashi remain essential tools for woodworking, bamboo crafts, and horticulture, specifically for grafting fruit trees and flowering plants. Kiridashi continue to be sought out for their excellent sharpness and blade quality.

Scissors are an everyday tool that cut using the shearing action of two blades. Blade alignment determines the sharpness of scissors, and the art of blade setting can take years to master.

Tsubame-Sanjo began manufacturing gardening scissors in the late Edo period (early-to-mid 1800s). When popular interest in flower arranging and bonsai trees took off in the Showa period (1926 – 1989), the industry grew, and scissor production flourished. Pruning scissors for flower arranging are especially diverse. Each of the nearly 300 schools of flower arranging around the country demand scissors with specific shapes and functions. Such variety is only made possible by hand manufacturing.

During the land expansion works of the Tenna era (1681 – 1684), Tsubame-Sanjo began to produce agricultural implements, work tools, and knives for daily life. Local hardware peddlers used the Shinano River to traverse the country, and Tsubame-Sanjo developed a nationwide reputation for knife production. Orders began to pour in for every type of knife, further fostering the region’s blacksmithing techniques.

The tradition of hand-forged knives, made by forge-welding red-hot steel onto soft iron, still lives on in Tsubame-Sanjo today. However, in the 1970s, stainless-steel manufacturing technology and the advent of “rikizai” (steel pre-rolled onto iron) revolutionized knife manufacturing. Now knives could be cookie-cutter “stamped,” or cut out of large sheets of metal. Rust-resistant, easy to handle knives flooded the market. The all-stainless kitchen knives that have become common in recent years were invented by adapting manufacturing techniques for making flatware. At the same time, traditional knife forging has begun to attract new attention for the high levels of technical mastery involved. In April 2009, Sanjo’s forged knives (known as “Echigo Sanjo uchi-hamono”) were officially designated as Traditional Craft Products of Japan by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI).

The carpenters’ square, or framing square, is an L-shaped metal rule used to measure and mark timber. Production in Tsubame-Sanjo can be traced back to the middle Edo period (1681 – 1780), although the hey-day of production wouldn’t come until 1893 with the implementation of new national laws. Later, as modernized building methods shifted toward little more than assembling pre-cut lumber, carpenters steadily had less and less need for framing squares. Shinwa, initially a producer specializing in framing squares, today also makes state of the art devices such as laser rules that project vertical and horizontal guides onto pillars, ceilings, and floors.

In 1661, the knowledge for manufacturing Japanese billhooks (“nata”) arrived in Tsubame-Sanjo from Aizu (western Fukushima). A common tool in mountain towns and farming villages, billhooks are smaller than axes and hatchets, making them ideal tools for clearing away small branches in woodland areas. Billhooks can also be used to easily split charcoal and firewood. The hey-day of billhook production came in the wake of WWII, during the reconstruction building rush. However, the introduction of chain saws and cheap imported timber made billhooks largely obsolete for industrial uses.

With the spread of mechanization, volume, speed, and affordability have become the key tenets of the manufacturing industry. However, some craftspeople in Tsubame-Sanjo continue to use traditional methods. Their tools are not only popular among professionals working in mountainous areas but also among outdoor hobbyists around the world. Recently, Japanese outdoor survival knives such as the tipped “ken-nata” and smaller “soenata” have been gaining attention.

There are few agricultural tools as unsuited to mass production as the hoe. Hoes vary in size and shape throughout the country due to regional differences in soil type, crop variety, and field work. For example, farmers in Tsubame-Sanjo’s home prefecture of Niigata prefer hoes with wide blades suited to hilling the soft soil in rice paddies. In the Kanto region, however, where soils are coarse, and vegetable fields are more common than rice paddies, farmers need hoes suited to digging and cutting. Until around the end of WWII, it is estimated that Japan was home to as many as 18,000 blacksmiths producing 10,000 different kinds of hoes. However, as farms mechanized, demand for hand hoes declined, and the number of smiths specializing in agricultural tools dropped throughout Japan. Over time, requests for tool repair work and new orders from people around the country started to flow into Tsubame-Sanjo.

Production of another important agricultural tool, the sickle, traces back to the 1650s in the early Edo period. Large increases in cultivated land acreage created new demand for farming implements. Tsubame-Sanjo’s smiths forged sickles for various uses, from cutting grass and weeds to harvesting rice. Eventually, the sickles from Tsubame-Sanjo would come to be used throughout Japan. As with hoes, sickles evolved to reflect regional differences in crops and vegetation. Although demand for sickles decreased with agricultural mechanization, Tsubame-Sanjo’s smiths continue to make sickles that meet the needs of users around the country. By continuing to produce agricultural tools, Tsubame-Sanjo helps preserve the diversity of Japan’s regional agriculture.

In 1625, a local governor promoted nailsmithing as a second source of income for farmers impoverished by frequent floods. This marked the beginning of the metalworking industry in Tsubame-Sanjo.

Around the same time, large fires in the capital city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) created a massive demand for nails, and blacksmithing flourished in Tsubame-Sanjo. Over the decades, Tsubame-Sanjo’s smiths used their knowledge from nailsmithing to begin manufacturing knives, copperware, and a large variety of other tools. When Western-style nails and architecture were introduced in the late 1800s, demand for traditional Japanese nails plummeted, and the number of nailsmiths declined. Today, only one traditional nailsmith remains in Tsubame-Sanjo.

However, the need for traditional nails has not disappeared. Japanese nails in many shapes and sizes are essential for restoring shrines, temples, and traditional buildings. Hand forged one-by-one, traditional nails are durable and resistant to corrosion. Today, the same techniques used to make Japanese nails are being used to make camping pegs strong enough to pierce asphalt.

Saw making came to Tsubame-Sanjo in 1661 from Aizu (western Fukushima) along with the knowledge for making files―essential tools for setting saw teeth. Repeated natural disasters in the late 1800s and early 1900s created a steady demand for saws and files. By around 1900, Tsubame-Sanjo was manufacturing as much as 80% of Japan’s saws and files.

For both saws and files, the setting of the teeth is a crucial stage of production. In saw making, craftsmen use a file to sharpen each individual tooth. For files, chisels are used to hammer teeth out of the steel one row at a time. File manufacturing also requires the use of other files―both to create ridges and to roughen the entire file surface for greater abrasiveness. Japanese file manufacturing features the unique step of applying miso paste to the file before tempering as a way of preventing carbon from clogging the file face.

With the spread of replaceable saw blades and a shift toward the growing Western cutlery industry, file production shrank and evolved. Today, Tsubame-Sanjo files are sought out by violin-makers and other craftsmen from around the world.

File making came to Tsubame-Sanjo in 1661 from Aizu (western Fukushima) along with the knowledge for saw making—files were essential tools for setting saw teeth. Repeated natural disasters in the late 1800s and early 1900s created a steady demand for saws and files. By around 1900, Tsubame-Sanjo was manufacturing as much as 80% of Japan’s saws and files.

For both saws and files, the setting of the teeth is a crucial stage of production. In saw making, craftsmen use a file to sharpen each individual tooth. For files, chisels are used to hammer teeth out of the steel one row at a time. File manufacturing also requires the use of other files―both to create ridges and to roughen the entire file surface for greater abrasiveness. Japanese file manufacturing features the unique step of applying miso paste to the file before tempering as a way of preventing carbon from clogging the file face.

With the spread of replaceable saw blades and a shift toward the growing Western cutlery industry, file production shrank and evolved. Today, Tsubame-Sanjo files are sought out by violin-makers and other craftsmen from around the world.

During the first half of the 1700s, Japan was the world’s top producer of raw copper. The Maze (“mah-zeh”) copper mine on Mt. Yahiko was especially well known for high-quality copper and drew coppersmiths all the way from Sendai. These smiths brought with them knowledge for copper hammering, a technique for shaping vessels out of a single copper sheet.

Copper’s superior heat conductivity makes it an ideal material for pots, kettles, and everyday tools. Even today, Japanese coppersmiths use hammers and metal stakes set in traditional sitting blocks to shape sheets of copper into finished works. Tsubame-Sanjo’s artisans also use tinning and patination techniques to produce unique and vibrant colors. During the second half of the 1800s, the coloring and hammer patterns of Tsubame-Sanjo’s copperware were highly appraised overseas, and coppersmiths began to produce works of fine art. Today, hand-hammered copperware is once again being made for daily use in the form of tea implements and sakéware, combining utility and artistry to create vessels that last for generations.

The kiseru is a smoking pipe for enjoying finely shredded tobacco. However, in the Edo and Meiji periods (1603 – 1912), the kiseru was not merely a tool for smoking tobacco, but also a popular fashion accessory and symbol of status. Samurai, merchants, and courtesans would often compete amongst themselves, hiring metal engravers to decorate their kiseru with elaborate, custom ornamentation.

The techniques for forming and engraving kiseru came to Tsubame-Sanjo in the mid-1700s. By the 1930s, Tsubame-Sanjo was producing 80% of Japan's kiseru. However, with the introduction of paper cigarettes after WWII, the demand for tobacco pipes declined dramatically. Today, only one artisan in Tsubame-Sanjo continues to produce kiseru by hand. Handmade kiseru pipes can be made thinner and lighter than mass-produced pipes―a highly valued quality among kiseru fans.

The manufacture of metal cutlery in Tsubame-Sanjo is said to have begun in 1911 with one order from Tokyo. The polishing techniques developed for kiseru tobacco pipes were applied to manufacturing cutlery, which quickly took root as one of Tsubame-Sanjo’s major products. After overcoming trade difficulties in the wake of WWII, cutlery from Tsubame-Sanjo spread into markets worldwide. Later, as emerging Asian countries came to prominence in the 1990s, Tsubame-Sanjo relied on quality and craftmanship for a competitive edge. Even today, experienced artisans can be seen hand-polishing products on factory floors. Tsubame-Sanjo’s polishers work with many types of pastes and over one hundred varieties of polishing buffs―ranging from rough and abrasive to silk soft―all carefully selected to suit the material, size, and shape of any workpiece.

When Japan opened to trade in the Meiji period (1868 – 1912), the copper utensils and kiseru tobacco pipes produced in Tsubame-Sanjo since the 1700s became export items. These products enjoyed high demand as gifts, and packing materials took on new importance. At the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair, the works from Tsubame-Sanjo were presented in beautiful wooden boxes that accentuated the value and appeal of their contents.

As the variety of products from Tsubame-Sanjo increased, so did the materials and packaging types. Today, Tsubame-Sanjo’s products use many different materials, including everything from paper and cloth to plastic and beyond. Tsubame-Sanjo’s packaging industry continues to work closely with factories and workshops to ensure that the products lovingly made by Tsubame-Sanjo’s craftspeople reach consumers’ hands in the best possible condition.

The first example of chemical coloring in Tsubame-Sanjo is said to have been conducted by hand-hammered copperware producer Gyokusendo in around 1860. Founded by Kakube Tamagawa, Gyokusendo initially only produced uncolored copperware for everyday use. However, the workshop’s second-generation head, Kakujiro Tamagawa, began incorporating various artistic elements. One such element was a decorative, red-brown patina called “sentoku.”

After cutlery manufacturing took root in Tsubame-Sanjo in 1911, it wasn’t long before manufacturers began applying brass plating. Tsubame-Sanjo’s first factory specializing in silver plating opened its doors in 1931. After WWII, stainless-steel replaced brass as the most common plating material, and by the 1970s, Tsubame-Sanjo’s factories were manufacturing stainless steel in a variety of colors. Today, Tsubame-Sanjo’s metalware products are finished using a wide variety of coating, plating, and oxidizing techniques.

The Tsubame-Sanjo area first began manufacturing metal dies as a tool for mass-producing kiseru tobacco pipes during the 1900s and 1910s. The industry progressed around 1930 when the artisans specializing in decorative engravings for copperware and kiseru pipes began cutting metal dies for cutlery. After WWII, metal stamping technology was applied to the manufacture of knives and work tools, allowing many products to be newly mass-produced.

Because dies are delivered to the client upon completion, diemakers only retain the manufacturing samples from testing the dies. While products with simple forms can be made using single-action dies, products with complicated forms are produced using what is called a “progressive die,” in which dies for multiple operations are evenly distributed within a single press, and parts are completed by undergoing successive stampings.

Die design requires the knowledge, experience, and creativity of an experienced craftsman. Today, dies support the manufacture of many of Tsubame-Sanjo’s products.

The history of metal cutlery in Tsubame-Sanjo can be traced back to a 1911 request for high-end cutlery from the Juichiya Trading Company in Ginza, Tokyo. Tsubame-Sanjo was already much lauded for its copperware, tobacco pipes, and engraving techniques. Cutlery manufacturing would require these skills, as well as the region’s polishing and forging techniques. Tsubame-Sanjo began manufacturing cutlery in 1914, and large orders started to pour in from Europe and elsewhere. Small home workshops began to open one after another in the area around modern-day Tsubame Station, laying the groundwork for the city’s current urban geography.

Shortly after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, a cutlery boom swept the nation, and Western-style cutlery found its way into Japanese households everywhere. Over the past century, Tsubame-Sanjo has continued to manufacture metal cutlery and currently supplies over 90% of the cutlery made in Japan. Cutlery comes in all shapes and sizes with many unique functional requirements. Tsubame-Sanjo’s manufacturers continue to meet these special demands, and many enjoy international recognition.

Metal spinning is a metalworking process in which a disk of sheet metal is spun on a lathe and shaped by applying pressure with a metal rod called a “spoon.” The trade is difficult, and artisans require years of practice. Although most metal spinners rely on dies and mandrels to shape workpieces, Tsubame-Sanjo’s artisans are also capable of free-form spinning. While metal spinning and metal stamping are both techniques that use pressure to shape workpieces, metal spinning excels at affordably producing small numbers of complicated forms.

Tsubame-Sanjo began producing metal homeware between 1947 - 1948 after receiving an order for cocktail accessories from US forces stationed in Japan. Metal homeware is a broad category that spans tableware such as plates, dishes, and cups to cookware and kitchen utensils. Tsubame-Sanjo’s factories took the stainless-steel manufacturing techniques they had developed for cutlery and applied them to homeware. Today, the cluster of homeware manufacturers specializing in stainless steel, copper, and copper alloy products in Tsubame-Sanjo produce over half of the homeware made in Japan. Their products are exported to 120 countries worldwide, with the greatest volume going to countries in North America, Europe, South East Asia, and the Middle East.

Tsubame-Sanjo’s history is one of industrial evolutions. With each new age, its manufacturers have pushed the bounds of their industries to answer the demands of the market. In recent years, Tsubame-Sanjo’s titanium tumblers have garnered attention. Light and strong, these tumblers use double-walled titanium vacuum flask technology for superior insulation. The tumblers were selected as a gift to leaders from participating economies for the APEC Japan 2010 conference in Yokohama.

After WWII, the introduction of machine presses created new possibilities for Tsubame-Sanjo’s metalworking industry. Although the region’s smiths had long produced traditional nails and carpentry tools, the new presses allowed workshops to manufacture a wide variety of machine parts and architectural hardware such as snow guards, supports for rain pipes, and kitchen equipment. However, a press with a precision die is not enough to produce durable, high-quality parts. The knowledge of an experienced craftsman remains essential. Even when working with a single metal, craftsmen must account for minute differences in thickness and hardness. Experienced craftsmen continually adjust the pressure and action of their press to suit each workpiece.

After WWII, the introduction of machine presses created new possibilities for Tsubame-Sanjo’s metalworking industry. Although the region’s smiths had long produced traditional nails and carpentry tools, the new presses allowed workshops to manufacture a wide variety of machine parts and architectural hardware such as snow guards, supports for rain pipes, and kitchen equipment. However, a press with a precision die is not enough to produce durable, high-quality parts. The knowledge of an experienced craftsman remains essential. Even when working with a single metal, craftsmen must account for minute differences in thickness and hardness. Experienced craftsmen continually adjust the pressure and action of their press to suit each workpiece.

From armor and farming implements to cars and home electronics, iron has long been an invaluable material. For Japan, with its scarcity of natural resources, iron has been especially precious throughout the ages. As early as the Edo period (1603 – 1868), Japan was home to metal recyclers called “furugane-ya,” who collected and resold iron from pots, kettles, and other tools. The old iron was remade into new tools in a cycle that still continues today. Research at Tsubame-Sanjo’s Obayashi archaeological site has uncovered a bellows tuyere and furnace walls used for bloomery smelting. The site dates to the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573), and it is believed that metal recycling was already being conducted in Tsubame-Sanjo at that time.